Why this is a must-watch Fed meeting

The Fed may raise rates again, but its signals on the banking crisis and future rate hikes will be key for the markets.

When the US Federal Reserve Board comes out with its latest decision on interest rates overnight, its actions—and words—will send a clear signal to investors as to what it views as the most severe risk facing the economy: financial stability or price stability.

Up until two weeks ago, Fed officials and investors had their attention fixed squarely on the battle against inflation.

Now, a banking crisis has unfolded with lightning-fast speed and led to both worries about the health of the financial system and a drastically changed equation for monetary policymakers who face an added layer of complexity in decision-making.

“Now they have conflicting objectives,” says Eric Winograd, chief US economist at AllianceBernstein.

“From a financial stability standpoint, they would probably prefer to pause, but from a macroeconomic standpoint, they would like to proceed with rate increases.”

For investors already wrestling with the implications of stubbornly high inflation and an economy running too hot for the Fed, the unknowns around the banking crisis also muddy the picture. The focus has turned from the Fed raising rates higher and holding them there longer to whether a credit crunch will tip the economy swiftly into a recession.

This leaves the outlook for the March Fed meeting decidedly more complex than it was just two weeks ago.

At that point, Fed Chair Jerome Powell had suggested that the Fed would ramp its tightening back up. Traders began betting that the Fed would revert to a half-point increase in the federal-funds rate, having slowed its pace to a quarter-point hike in January.

Will the Fed Raise Rates or Pause?

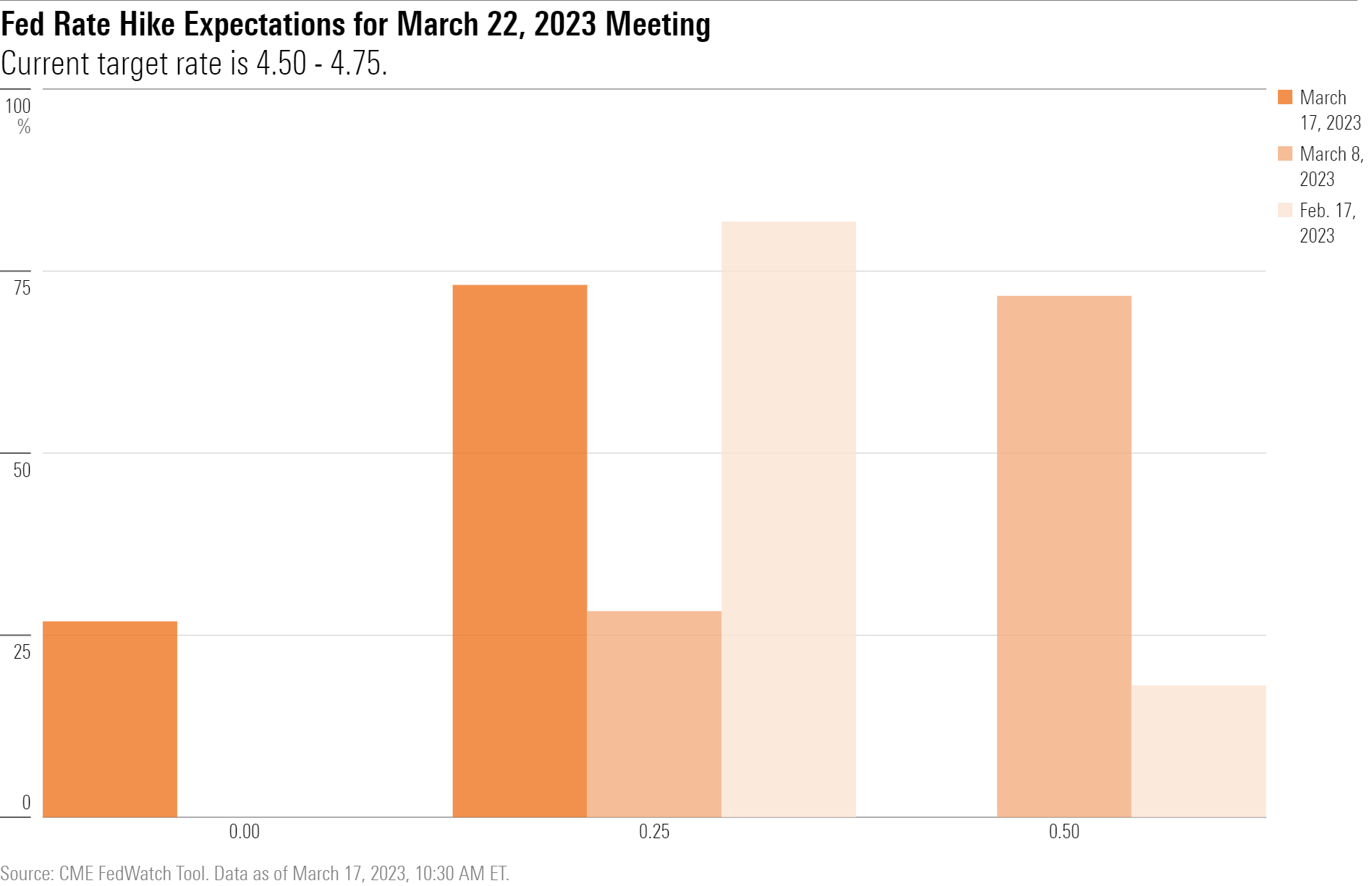

But now, the bond futures market, where traders make bets based on the direction of interest rates, is suggesting that a quarter-point increase is the most likely outcome, with a distinct chance of no rate hike. And just as important, investors will be looking for any hints that Fed officials think that ongoing interest-rate increases are—or will soon be—off the table and that the next move will be for rates to head lower.

A bar chart showing how expectations for the Fed's next move have altered considerably because of the bank crisis.

However, the efforts by the Fed and the banking industry to contain the crisis could actually keep the Fed on its rate-hike trajectory, just at a more moderate pace, says Morningstar chief US economist Preston Caldwell.

The current “financial distress argues for a continued slow path for rate hikes with a 0.50% hike out of the question” as long as the Fed “can combat any crises by providing adequate liquidity.”

Caldwell projects the federal-funds rate will be at 4.75% by year-end 2023—the current target is 4.5%-4.75%—and inflation to fall to the Fed’s target rate by year-end 2024.

Whatever course the Fed takes, when Powell speaks to the press following the meeting, investors will be expecting a clear and full explanation as to what factored into its decision and how it expects to proceed going forward.

Key items to watch from the March Fed meeting

- Does the Fed pause its rate hikes?

- Is the Fed prioritising inflation or financial stability?

- How worried is the Fed about the banking system?

- Is the Fed seeing signs of a credit crunch?

One group that has concluded that the Fed’s work is done: bond investors.

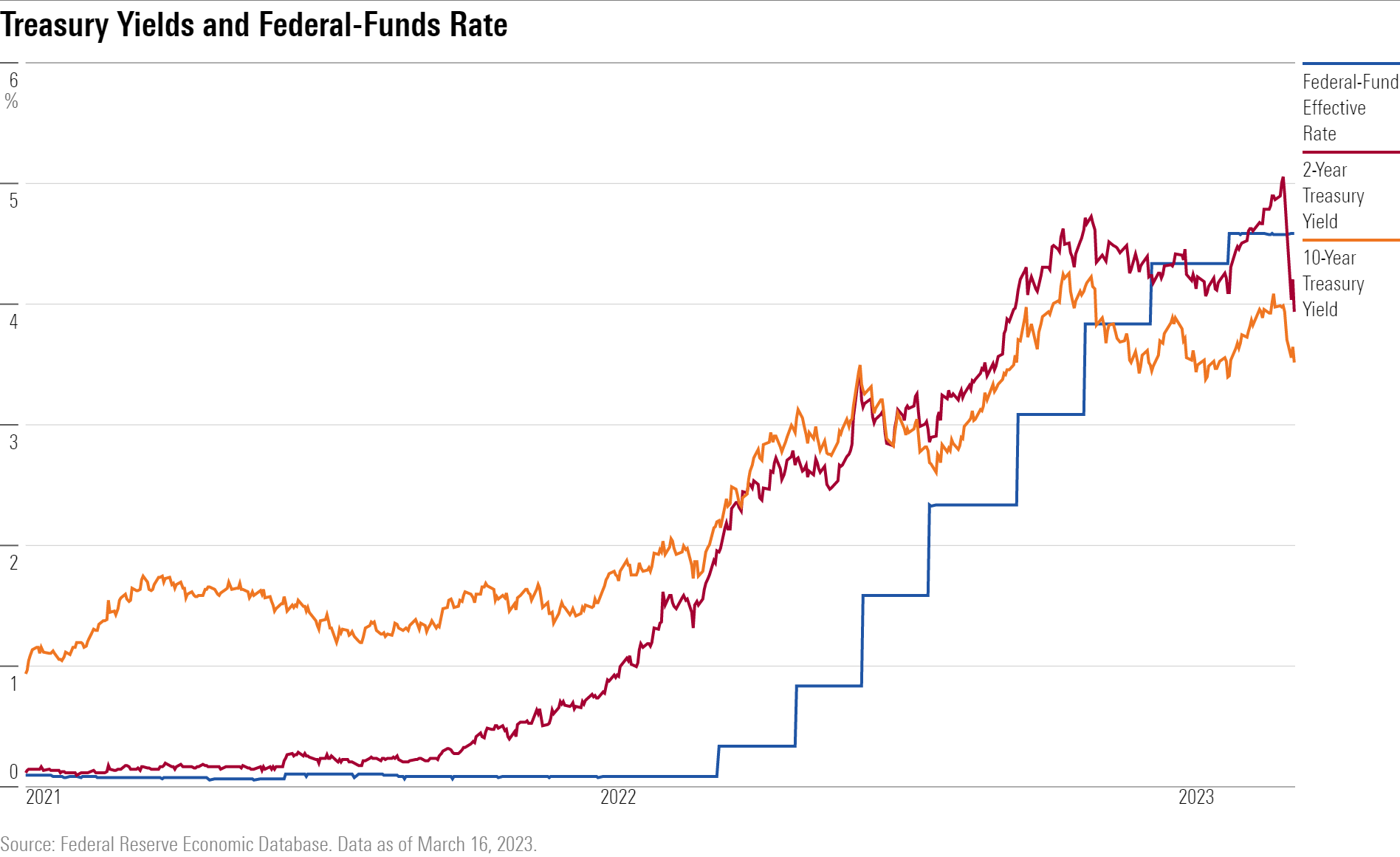

The yield on the two-year US Treasury slid to 3.95% last week from more than 5.00% a week earlier.

Within a three-day-period, it lost about 1 percentage point, marking the biggest decline since the October 1987 stock market crash.

Investors rushing to the safety of government securities pushed prices up and yields down (bond prices and yields move inversely to each other) as concerns about the banking system spread.

Fed balancing inflation vs. financial stability

The central question facing the Fed is what to do with interest rates at a time when the current economic data shows continued strength and inflation well above the Fed’s target, but stresses in the banking system threaten to derail growth.

“The policy decision is always about the balancing of risks,” says William English, professor in the practice of finance at Yale School of Management and former deputy director in the Division of Monetary Affairs at the Federal Reserve Board in 2008-10, during the global financial crisis, before being elevated to division director in 2010.

As evidence of the dilemma facing the Fed, even as headlines blared about the risks boiling over in the banking sector, the February Consumer Price Indexcame in at a still-hot 6% annual rate this past week.

“A lot of the data points to stronger-than-expected inflation,” says English.

Adding to the Fed’s challenge: key data released late last week that showed the economy continues to run at a frothy pace. Weekly jobless claims posted the biggest drop since July. Housing starts surged 9.8% in February to the highest level since September, and overall building permits saw a 13.8% rise.

But the banking crisis, which raises the risk that banks will pull back significantly on lending to businesses and individuals, could be worsened by continued interest-rate increases.

Fed to Weigh Signs of Banking Stress

One piece of important information that the Fed most certainly will take into account: Borrowings from the Fed’s discount window ballooned in the past week by $148.2 billion to about $152.853 billion from $4.581 billion on March 8, according to data released by the Fed on Thursday. The so-called discount window is a way for the Fed to provide short-term loans to financial institutions to help manage liquidity risks and ensure stability in the banking system.

Financial institutions also borrowed $11.9 billion in one-year loans under the new Bank Term Lending Facility established less than a week ago to ease any liquidity pressures related to the current crisis, according to data released Thursday by the Fed. Another $142.8 billion in credit was extended to the bridge banks related to the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank.

“The large amount of borrowing makes clear that there is a lot of stress in the financial system,” says Winograd of AllianceBernstein.

“What happens in the next few days will determine the outcome of the Fed meeting. The more money they have to lend, either through the window or the BTFP [Bank Term Funding Program], the more systemic stress it will reflect and the less likely it will be that they raise rates.”

In the past, banks have been reluctant to tap the discount window because of concerns of the stigma attached. Yet, with so many banks already seen as being in trouble, that may not have played as big of a role in their willingness to go to the window, says Winograd.

The big increase in the discount window borrowings is a “sign that banks are under pressure,” says English of Yale School of Management, but also reflects that the Fed made the terms to borrow easier.

Credit crunch could limit Fed rate increases

Jeff Schulze, investment strategist at ClearBridge Investments, says the Fed ultimately may have less tightening to do as a result of the bank crisis. He expects a quarter-point rate increase at the March meeting.

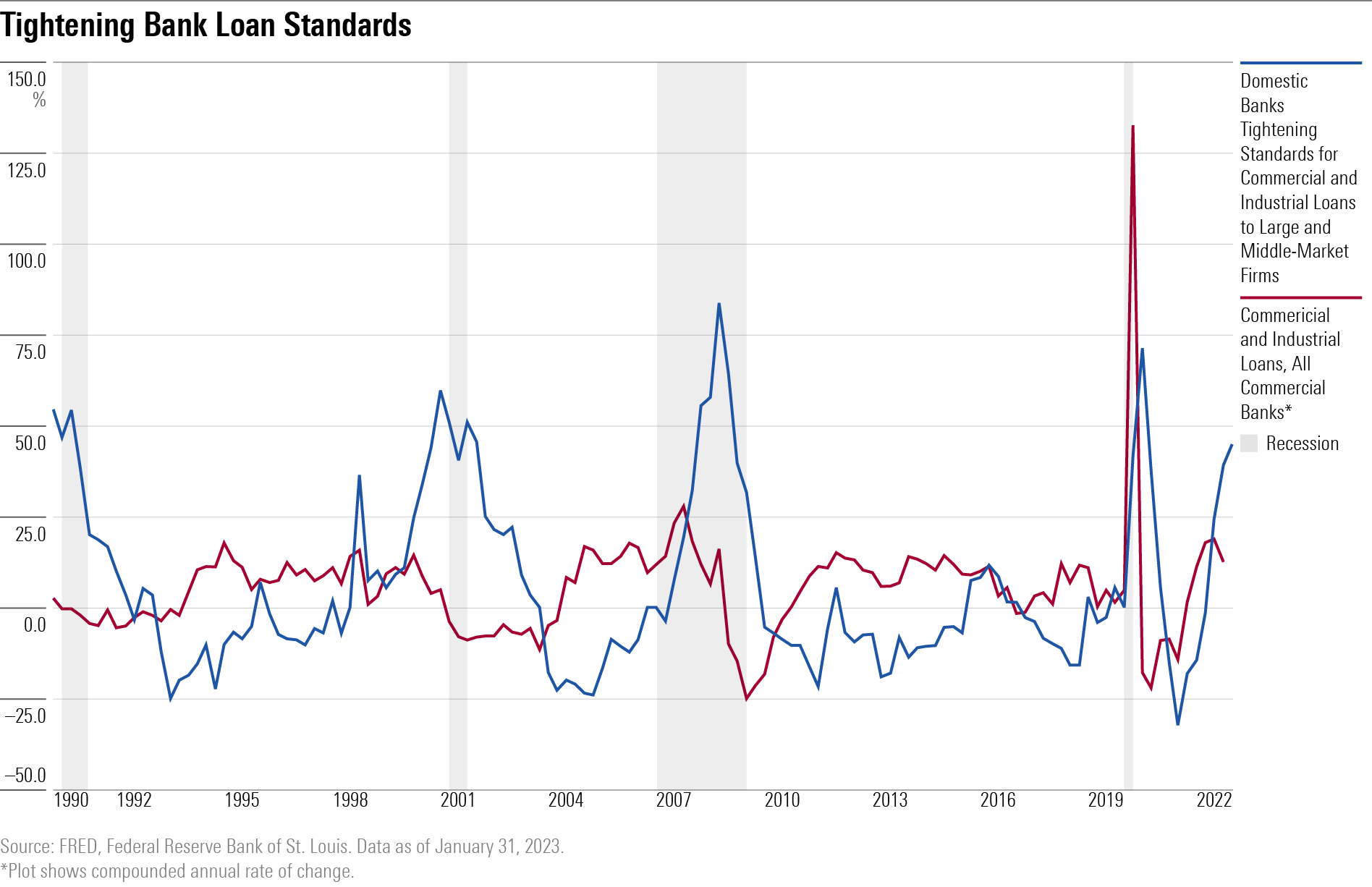

“It appears likely credit will further contract in the coming months as banks focus on survival rather than loan growth,” he says.

“Lending standards will tighten further, meaning less access to credit for borrowers and a higher cost of capital, resulting in slower economic growth. This reinforces our long-standing view that a US recession is on the horizon.”

In fact, banks and consumers had already begun pulling back even before the emergence of the banking crisis.

According to the Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey compiled by the Federal Reserve in January, banks reported tightening lending standards as well as weakening demand for commercial and industrial loans, household loans for residential real estate and home equity lines of credit, and credit card and auto loans, among other consumer loans.

That dynamic could lead the Fed to pause next week, an action he sees as the second mostly likely outcome behind a quarter-percentage-point hike.

John Briggs, global head of economics and markets strategy at NatWest Markets, makes the same point about banks pulling back on lending activities.

In the wake of the banking crisis, he says, “a small or midsize bank is going to be more likely now to deny a loan to that dry cleaning business that wants to open up than from a week ago.”