5 reasons why airlines don't have economic moats

Structural factors such as competition and fuel costs make it difficult for carriers to generate excess returns.

Mentioned: Air New Zealand Ltd (AIR), Air New Zealand Ltd (AIZ), Qantas Airways Ltd (QAN), Regional Express Holdings Ltd (REX)

The term “wide moat” is Warren Buffett-speak for competitive advantage. According to Buffett’s medieval metaphor, a wide moat is a company’s ability to withstand rivals—the same function a moat serves in protecting a castle.

“The key to investing,” Buffett wrote in a celebrated 1999 article in Fortune magazine, “is determining the competitive advantage of any given company, and, above all, the durability of that advantage.

"The products or services that have wide, sustainable moats around them are the ones that deliver rewards to investors.”

Morningstar has used the moat concept as the foundational pillar of its stock analysis method. Analysts look for five characteristics when deciding whether to give a company a moat: intangible assets like brand or parents, cost advantage over rivals, switching costs to keep customers from changing providers, network effect and efficient scale.

MORE ON THIS TOPIC: Morningstar's eleven: How to spot a wide-moat stock

However, Morningstar equity analysts have declined to grant economic moats to major global airlines. Analysts cite several structural factors including the fiercely competitive nature of the international travel industry, unpredictability of events that destroy investor capital and management's limited control over key external earnings drivers like fuel costs and exchange-rate movements.

"Airlines have traditionally been an industry where a no-moat rating is almost too generous, with an infamous history of value destruction as measured by subpar returns on capital," says US equity analyst, aerospace and defence, Burkett Huey.

"In our view, there are structural factors that make it difficult for airlines to generate excess returns: a mostly undifferentiated product, a tendency for irrational competition, substantial operating leverage, and a tendency to employ financial leverage that exacerbates booms and busts."

After a year to forget for airlines, including Virgin Australia's slump into administration and sale to US private equity firm Bain Capital, we asked Morningstar Australia equities analyst Angus Hewitt if this had altered his view on the moat rating of Qantas (ASX: QAN) and Air New Zealand (ASX: AIZ).

"No, is the simple answer."

Here's why.

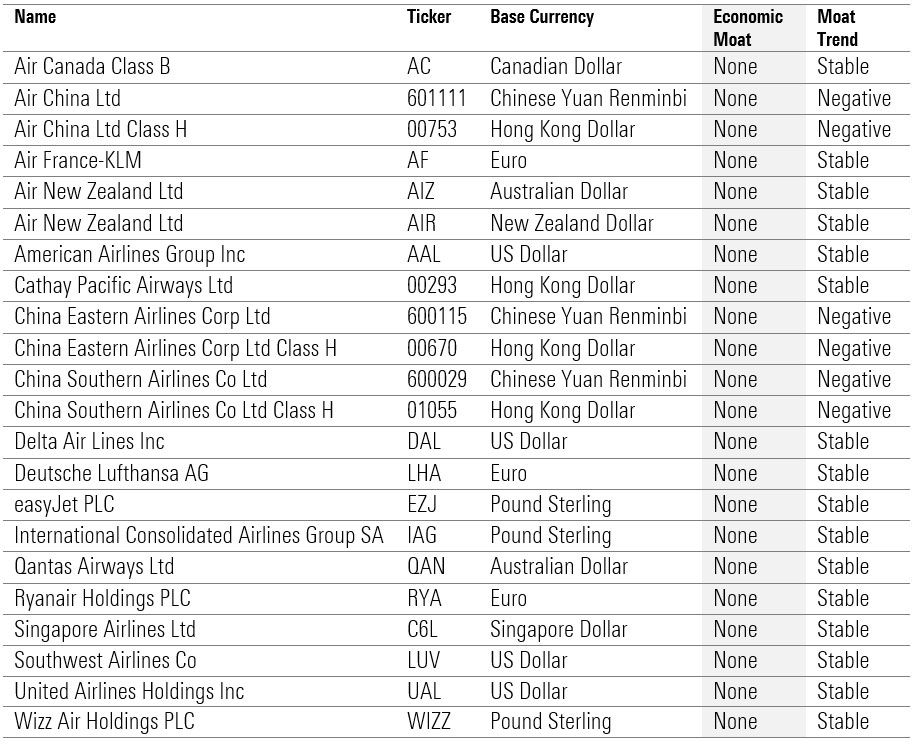

Moats | Morningstar equity global airline coverage

Source: Morningstar Direct

1. The commoditisation of air travel

You need to fly from Sydney to Melbourne. Both Qantas and Virgin offer a flight at the same time. Which one do you choose? The cheaper one, right? Hewitt says Qantas is selling a commodity good in a highly competitive market and cannot rely on cost advantage or switching costs to build a moat.

"Air travel is perceived as a standardised product which, coupled with price transparency, leads to low switching costs."

Australia's domestic air travel market is effectively a duopoly between Qantas (including budget airline Jetstar) and Virgin Australia. Virgin Australia entered voluntary administration in 2020 but has re-emerged under private equity firm Bain Capital. Smaller regional player Rex is aggressively taking aim at Australia's aviation industry with flights between what's referred to as “the golden triangle” – Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane – but its success remains to be seen.

In light of industry disruption from the pandemic, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission has been tasked with keeping a close eye on the domestic competitive environment as demand returns

"The ACCC doesn't want to see Qantas squash Virgin and Rex before they get their wheels off the ground," Hewitt says.

"They'll be watching for things like dumping capacity and slashing prices to ensure that competition remains a feature of the domestic industry."

2. A business model not conducive to rational pricing

Hewitt notes that the international segment is fiercely competitive with many carriers adding capacity to and from Australia in recent years, weighing on Qantas' returns. This, he says, creates downward pressure on ticket prices, as evidenced by Qantas International's falling yields.

"This elevated competition on international routes is reflected in the division's 15 per cent EBITDA margin, which is lower than the 26 per cent generated in the Qantas domestic division," he says.

"Although movements in oil prices often lead to short-term swings in return on invested capital, we believe carriers' long-term profitability has little to do with fuel given the cost affects all players almost equally.

"Reductions in fuel (or other input costs) are typically competed away, and savings are passed through to customers, reflecting the extremely high level of competition in the airline sector."

The situation for AIZ is similar, Hewitt says, where many carriers have aggressively added capacity to the trans-Tasman route. This route accounts for around two thirds of the national carrier's revenue weighing on returns.

3. The presence of low switching costs coupled with growing price transparency

Qantas has attempted to garner customer loyalty with its frequent-flyer programs. Frequent-flyer programs incentivise customers to fly with a particular airline.

"Consumers want to earn loyalty points when they fly, and status benefits are important for corporate passengers," Hewitt explains.

"The program generates earnings from the sale of points to hundreds of partners, including banks, supermarkets, and department stores."

Hewitt says that while the capital-light Qantas Frequent Flyer business has somewhat cushioned Qantas's flying earnings volatility, he doesn't believe it has carved switching costs.

"If you're part of a frequent-flyer program you'll probably be more 'stickier' to Qantas but there's a limit," he says. "How much extra are you going to pay to get those points? Maybe an extra $20, but $50 or $100? Probably not."

4. A long history of value destruction

The global pandemic is fresh is everyone's minds. Australia's stringent entry requirements for international arrivals, a ban on noncitizens, and domestic border closures have grounded Qantas's fleet, destroying value almost overnight. But Hewitt says unpredictable events are part and parcel of the airlines business.

"A global pandemic isn't something we expect will be a regular occurrence, but demand disruptions are common within air travel," he says.

"Terrorism, war, natural disasters, and epidemics. Investors will remember the impact that events like SARS and 9/11 had on people's desire to hop on a plane. These events crunch travel demand, almost instantly."

Hewitt says the highly capital-intensive and extremely cyclical nature of the business, particularly airlines’ exposure to the volatile fuel price, makes them prone to value destruction.

"During the 10 years ended fiscal 2020, Qantas has incurred almost $7 billion, cumulatively, in write-downs, impairments, and restructuring charges," he says.

"The most noteworthy was the almost $3 billion fleet write-down in fiscal 2014, and more recently the $1.4 billion impairment (mainly to the A380 fleet) in fiscal 2020."

5. Lack of barriers to entry

"Buy a plane and you're ready to go". Well, it's not that simple, but Hewitt notes that the barriers to entry for new airlines are low. Higher capital requirements are among the biggest sticking points. For a relatively mature market, Australia has seen several new entrants. Virgin touched down in here at the turn of the century. Since then, we've seen low budget airline Tiger and now Rex making a play for the Australian market. Bain too is effectively "entering" the market.

While new domestic entrants in the small Australian market are not commonplace as say buy now pay later companies, globally, new entrants enter on a regular basis. 2020 has understandably been a slow year for airlines but several still came to market, including start-up South African low-cost airline LIFT Airline, Vietnamese leisure airline Vietravel Airlines, and Swedish Virtual airline Air Gotland.