Uncertainty reigns in commercial property

The corona crackdown is robbing malls of their customers and that is putting pressure on their outlook.

Mentioned: Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield (URW), Goodman Group (GMG), Scentre Group (SCG), Vicinity Centres (VCX)

Retail property investors could be staring down the barrel of dilutive capital raisings as shopping centre landlords fight for survival amid the coronavirus pandemic.

While Morningstar equity analyst Alexander Prineas expects landlords to pull through the crisis, with most tenants tied to iron clad long-term leases, he anticipates a dramatic reduction in earnings could force some to raise capital to shore up their balance sheet.

"The issue is that landlords are up against it as well," he says. "A lot of them are in large amounts of debt and they have to meet their obligations.

"For now, it's not a question of survival. It's a risk, yes, but more likely companies would have to do a dilutive capital raising. Somebody will get the benefit of the recovery in those assets, but it just may not be the current shareholders."

When a company issues new equity to raise capital, existing shareholders own less of the company. That means their share of earnings and dividends is also reduced.

Prineas insists that this is not his base case. Morningstar believes landlords across the sector will pull through and get back to an approximately normal situation. Tenants, they say, are locked into long-term leases that renew only every five to 10 years, so only about 13 per cent of the REITs' tenants are up for renewal in a given year.

"As long as this event doesn't dramatically shift all consumer behaviour to online shopping, the long-term cash flow outlook should be relatively intact."

If the virus is prolonged, leading to bankruptcies, analyst say the possible reduction in occupancy rates could take time to replace, which would have a significant short- to medium-length impact. Capital raising is certainly a risk.

Before things get to that point, Prineas says firms can employ several offset measures, including cutting costs, delaying development spending, cancelling share buybacks and seeking government support. He also anticipates dividend cuts.

"The main thing for these firms to do is to try and avoid triggering their banking covenants – or giving into financial stress," he says.

Sit and talk

As Australia ushers in strict new social distancing rules, shopping centres are turning into ghost-towns, and shop owners are on the front line of the crisis.

Major retailers are closing their doors or publicly threatening to go on a rent strike. The escalating problem now has government urging landlords and tenants to work together in return for direct assistance.

But Prime Minister Scott Morrison warned on Friday that Australia's retail slump would be a "burden for everyone to share". "Some landlords will suffer and banks will have to make arrangements with them," he added.

In Asian markets such as Singapore, REITs have rolled out several measures to help their tenants affected by the coronavirus outbreak including passing through the 15 per cent property tax rebate provided by the government to the affected tenants.

In order to ease the short-term cash flow challenges of their tenants, some trusts allowed the use of one month of security deposits to offset rent, while others allowed tenants to convert security deposits into banker's guarantees.

Some trusts are providing up to half a month of rental rebates to affected tenants. In order to increase footfall and sales, the trusts have increased marketing efforts by giving additional promotions and rebates as well as free parking at selected hours to try to attract people to visit and spend at the malls.

While many firms look cheap compared to Morningstar's fair values, Prineas advises binvestors to act with caution.

"A lot of uncertainty remains in the sector," he says. "Retail is generally discretionary, and a typical mall will devote at least a segment to luxury.

"While the health effects of the virus may be dealt with, the wealth effect may take longer to recover."

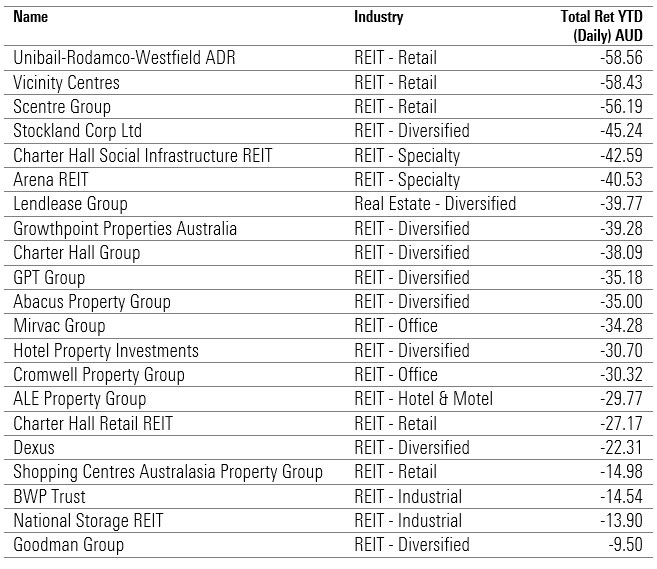

Year-to-date, Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield ADR (ASX: URW) has been hardest hit, returning –58.56 per cent, followed by Vicinity Centres (ASX: VCX) and Scentre Group (SCG). Industrial property firm Goodman Group (ASX: GMG) is among the most protected, down –9.50 per cent since the start of the year.

Sector Performance: Real Estate, return YTD (under Morningstar coverage)

Source: Morningstar Direct

Supply demand disruption

For commercial office space, Prineas says landlords are facing many of the same issues as retail but to a lesser severity. But what concerns him most is that the crisis could kick off a series of rental renegotiations in markets where demand was already outstripping supply.

"If the tenant is not using a space for months on end, it's hard to imagine that's not going to kick off rental renegotiations," he says.

"The issue that office sector was extremely tightly supplied, and rents had gone up to eye-watering levels the last few years in Sydney and Melbourne CBD, particularly in A-grade and premium grade office.

"The risk here is that some of that rental tension is taken out of the market."

Prineas says that office landlords are in reasonable shape to weather the near term, but longer-term there are concerns that supply and demand could become more evenly balanced.

For co-working spaces, Prineas says demand will likely evaporate with long-term leases not built into the business model.

"Co-working spaces talk about the benefits of being located with other creatively minded business," he says. "I haven't seen a lot of evidence that tenants will pay more for that.

"What they're really paying for is the flexibility – the ability to take office space when they need it and not pay when they don’t."

This time it's different

Long-term investors will likely draw connections to the financial crisis 12 years ago which saw retail investment trusts (REITs) among the hardest hit. However, Prineas says the harsh lessons learned during the 2008 global financial crisis mean that most REITs have been exceedingly cautious with their balance sheets and are conservatively positioned.

"When the GFC hit, REITs had very high debt and a lot breached their banking covenants. That meant that credit lines were withdrawn, and the banks were enabled to force them to sell assets, which in the GFC meant they'd have had to sell assets at a massive discount because there were no buyers," he says.

"Most of the REITs did very dilutive rights issues, and although REITs rebounded strongly after the GFC, the shareholders invested before the crisis didn't get anywhere near as strong a rebound.

"But now, REITs do have lower debt and are conservatively positioned."

Prineas says pockets of stress will however emerge if the outbreak intensifies, particularly if asset values fall.

"On a debt-to-assets metrics REITs look more conservative than the GFC, but if the asset values fall, suddenly their debt can look high. Falls in asset values are a risk.

"Falls in earnings are also likely and some of the REITs do have covenants relating to having their earnings a certain amount above their interest payments."

Nearly all REITs have withdrawn their guidance for the current fiscal year.