Unfortunately, all fund manager presentations are good

Part of the fund manager's job is to raise money from investors, and with years of practice, a few good stock stories and an educated guess on the future, it's not hard to present well. That's a problem for investors.

Part of a portfolio manager’s role is generating inflows to their fund, raising new money and retaining clients by telling a captivating story. Month after month, year after year, the presentation skills are refined. For the most part, the managers enjoy the work, the enthusiasm is genuine and there’s always a story to tell. They are smart people, as becoming a portfolio manager requires a lot of study, time in the job, market analysis and experience, and beating others for the top gig.

They routinely update their professionally-designed Powerpoint presentations with charts that support a compelling narrative, and after adding a table showing a successful overweight stock position or two, they're off to the races. And don't forget to smile confidently and thank everyone for their attendance.

Investors love stock stories

Most fund managers have talked the talk and walked the walk hundreds of times. They have the advantage of an interesting subject matter, especially stock stories. Even a fund manager who is underperforming across a portfolio of say 30 stocks will have a few big winners. Attend any conference where a fund manager is speaking about stocks and watch the audience members taking copious notes. People love stories about stocks, and fund managers feed the need by explaining how they picked up a company for $1 and a year later, it is $3. It shows their skill in selecting companies, and retail investors hope the magic dust will sprinkle on them.

What is not said is that there are at least as many dogs in the portfolio, but let’s ignore them and focus on the good bits.

Combine long-term experience delivering a similar message, a subject matter that attracts a cashed-up audience and a public profile, and it’s a recipe for universally-strong presentations.

I attend a hundred of these events a year and I have probably heard a thousand in my life. I listened to three last week and they were all interesting. Based on what was said and no further research, I would be happy for any of the presenters to manage my own money.

And that’s the problem. There’s no such thing as a bad presentation. All Chief Investment Officers can make a convincing case that their fund is about to deliver strong results. Unfortunately, investors should not simply hand over their hard-earned on basis of a presentation.

Magellan’s success based on Hamish’s presentations … after six years

Who is the highest profile and arguably most-successful portfolio manager in Australia? I nominate Hamish Douglass, who has built Magellan into a $100 billion investment powerhouse and introduced many market innovations. Hamish came from an investment banking background and was always a polished and persuasive performer. You would think a fund manager like Hamish would experience instant success and a big following from Day 1.

Magellan was established in September 2006, but it did not establish a meaningful reputation among advisers and retail investors for many years. I recall an early presentation in the Magellan office where Head of Distribution, Frank Casarotti, struggled to attract more than 20 people. It was social distancing before we knew the meaning of the words. As Casarotti describes in this article from 2016, Magellan did not have a month of retail flows over $50 million until 2012. That’s six years of excellent presentations and strong results before significant retail inflows were generated.

One reason for the slow inflows (and a little matter called the GFC) is that despite the quality of Douglass’s presentations, they were not materially superior to many others. It's difficult to really stand out in an impressive group. It was the combination of results and marketing over a long time which created the Magellan success story and the Douglass reputation.

Practice makes ... pretty good

In the mid-1980s, when I was Head of New Issues at the Commonwealth Bank, I undertook a fund-raising roadshow in Hong Kong and Singapore with Deputy Treasurer, Paul Skerman. We booked over 30 meetings in a hectic week, including breakfasts and dinners. Prior to the trip, we practiced our presentation several times, including where to pause, when to smile or nod, who would say what. Paul focussed on the big picture while I talked about the balance sheet and the transaction.

By the middle of the week on the road, I could have done the presentation in my sleep. Maybe I did, because after a couple of days, Paul asked me to smile more and look enthusiastic when he was talking. It was a good lesson. Approach every meeting as if it were the most important, as if the subject were fresh. We might hear the patter dozens of times but everyone else would only hear it once.

By the time we left Asia, we knew all the questions, all the answers, and it went like clockwork. It’s not that we were especially good presenters, but there was a lot of interesting material backed by plenty of practice. I’m sure it was a good presentation and the transaction went well.

What if a fund is underperforming?

Surely it’s not possible for a fund manager to make an impressive presentation if their fund does not have a good recent track record.

Paul Fiani founded Integrity Investment Management in 2007. He had previously shot to prominence while at UBS Asset Management when he took a strong stance against a private equity bid for Qantas. In the early years, Integrity won a number of awards and at its peak was managing over $5 billion.

I was at Colonial First State when we took Fiani on a national adviser roadshow, a prized role for any fund manager as the adviser exposure was unequalled at the time. However, Fiani had experienced a run of underperformance, as happens with all managers, and I was intrigued by how he would explain the poor numbers.

Fiani was a good presenter, and watching the advisers in the room, he held their attention as he talked the stock stories they all love. Then came the crunch slide on Integrity’s performance, but Fiani did not miss a beat. He explained that the best time to invest with a fund manager was not when they had just done well, as all their bets had already paid off. It’s when they have done badly, because investors gain exposure to companies before the share prices improve.

It was brilliant. He made the poor performance into a big plus, and the advisers around my table nodded their agreement. (Footnote: for various reasons, Integrity closed in 2017 and returned all money to its investors).

Value versus growth presentations in the current day

The last few years have challenged traditional ‘value’ managers who select companies based on fundamental assessments of intrinsic company value versus current market price. In contrast, ‘growth’ managers buy expensive stocks when they can see the future potential with profits in the distance. The best examples are tech stocks trading on extreme price multiples but with exciting prospects. Value managers argue they are priced for execution perfection and it’s better to stick to proven companies making real profits. Growth managers believe the dream.

Within the space of two days recently, I listened to a value and a growth manager and both were persuasive.

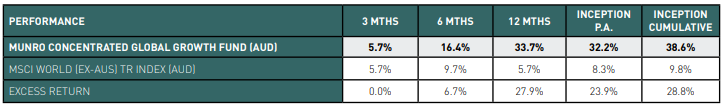

The growth manager was Munro Partners’ Chief Investment Officer, Nick Griffin. In this climate, growth managers are delivering impressive results and loving that their investment approach is vindicated. Munro’s Top 5 investments are Amazon, Microsoft, HelloFresh (food delivery), ServiceNow (digital workflows) and Taiwan Semiconductors. Strong results were also delivered for the portfolio by chipmaker ASML and Vestas Wind Systems. Munro’s investments are dominated by tech, climate change and e-commerce, and here are the strong results.

Griffin’s Global Growth Fund picks from the best companies in the world according to themes which he believes are changing the ways we live and delivering outstanding company opportunities.

It is a classic growth story, believing in the promise of the future, and Munro has enjoyed the market run with a handsome 34 per cent return over the last year, a long way above its benchmark. Griffin has great optimism in market conditions over 2021 and his ability to select the winners.

The second presentation was by Schroders’ Martin Conlon who has been Head of Australian Equities there since 2003. A focus on the Australian market is a headwind in the current conditions, as the local market does not have the tech and health sector titans which have driven US markets. The broad Australian index was flat for 2020. Schroders is more of a traditional manager, which:

“… seeks to focus on the fundamental risk inherent in a business and the way it is financed rather than focusing unduly on the range of emotional and non-fundamental factors which drive day to day share prices.” (Source, Schroders Wholesale Australian Equity PDS, 1 October 2020).

On 10 January 2021, Conlon wrote:

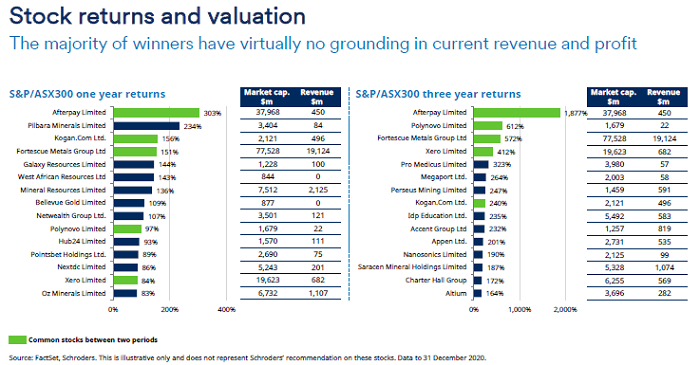

“There is some bitter irony in large pension funds observing the crazy punting of Tesla in the US by the Robinhood Army, only to buy it themselves at much higher prices when S&P tells them. Domestic poster children remained the usual suspects; Afterpay (+47.5 per cent) and Xero (+45.7 per cent) in tech, Polynovo (+75.6 per cent) and Nanosonics (+41.4 per cent) in healthcare, not to mention a healthy dose of lithium and rare earths. The durability and quantum of gains from some of these thematics continues to embolden investors. Our assessment of the odds remains one in which luck and a few hot hands are being confused with mastery of the game. It is behaviour creating the apparent value, not fundamentals.” (my bolding).

Last week, he presented two charts which show how current prices are frustrating his process. He said:

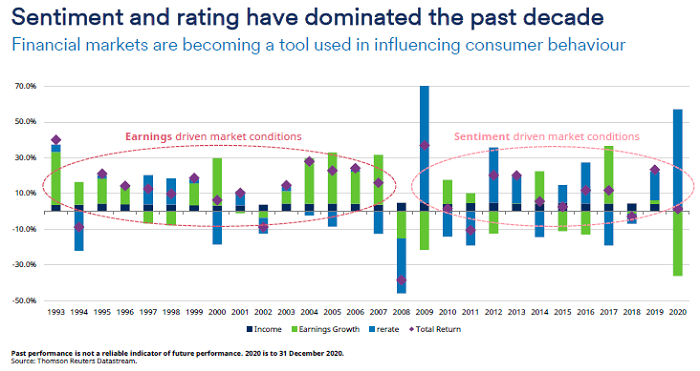

“Equity market returns in the past decade have transitioned from being earnings driven to ratings driven. Expansion in the rating attributed to earnings, or in some case revenues given the absence of profit and cashflow, has become the dominant driver of share prices. This is most evident in technology where multiples and valuations are almost certainly in bubble territory, however, most stocks with perceived growth in revenue and expectations of future profit growth remain priced at levels vastly above historic norms.” (my bolding).

This chart of market performance shows how earnings growth (the green bars) dominated returns from 1993 until the GFC in 2008, and how rerating (the blue bars, where the market is paying more for the same earnings) have generated returns more recently.

Schroders also provided the following chart which shows: “The majority of winners have virtually no grounding in current revenue and profit."

And fair enough. It was a good presentation showing the market is overvalued and stocks have insufficient revenues to justify their prices. Conlon is in solid company with many prominent investors, such as Investors Mutual, Lazard and Maple-Brown Abbott, arguing the same point.

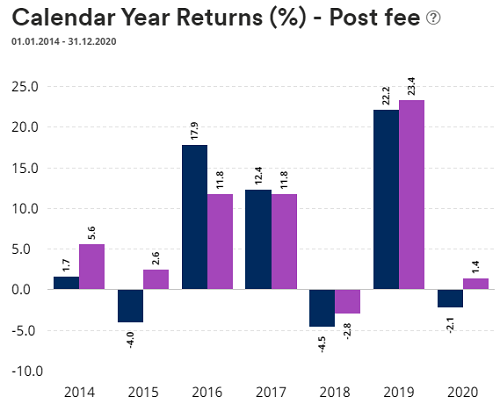

How has Conlon’s fund (the dark blue bars below) performed versus its benchmark (the purple bars)? After fees, it is under its benchmark in each of the last three years, cumulatively by 6.4 per cent. Market conditions have not suited this type of manager, and he has explained why. Job done and everybody is happy because he has stayed true to his style.

Investing is about the future

In two good presentations, one manager sees a bright future for many high P/E stocks and backs his growth thematics, while another sees investors pumping money into recent winners regardless of price and value, and at some stage, the market will come to its senses.

Who is right? I have no idea. Ask me in five years when we can look back on Munro and Schroders.

The point is that both presentations were impressive. What should an investor do?

- Back the recent winner whose style will continue to pay off, or

- Back the recent loser whose style is about to pay off?

So if you can’t tell from the quality of the presentation who to invest with, how do you select a manager? Cofounder of this publication, Chris Cuffe, has spent a career selecting managers, and his coverage of the subject is here and here and here. Chris primarily backs long-term performance and ignores numbers over less than three to five years. His ‘for charity’ Third Link Growth Fund has an impressive track record by outperforming its benchmark by 3.5 per cent per annum compound since May 2008.

In the meantime, sit back and enjoy the fund manager presentations. They are all good although not decisive in the investing decision. Lap up the stock stories (you know you love them, even if you’re not sure why or what to do with them), follow the pretty charts, hear the well-practised patter and nod sagely.

And if you do give the fund manager your money, consider it a 10-year commitment because that’s how long it will take before you know if they have talent or luck.