Why factor analysis supports Jack Bogle’s key principles

Vanguard's Jack Bogle was correct that costs do a better job of forecasting future net returns.

Vanguard Founder Jack Bogle had many views, all pronounced. He criticised publicly traded mutual fund companies and exchange-traded funds, supported stricter fund regulation, and pooh-poohed international stocks.

However, he is best remembered for three claims:

- In aggregate, funds keep pace with the indexes before paying their costs but lag afterward;

- Because fund returns are unpredictable, there’s not much point in picking winners; and

- If success does endure, that result is likelier to owe to low costs than to portfolio-manager skill.

None of these tenets were invented by Bogle. They came from academic research. But unlike most other industry executives, Bogle heeded the professors’ teachings. He was their great populariser.

Factor Models

It is fitting, then, to test his claims with another academic invention: factor models. (For nostalgia’s sake, I attach an old paper on the topic, from when I studied for the chartered financial analyst designation.)

Factor models attempt to assess the degree to which investments are affected by various market trends, or “factors.”

When applied to funds, factor models work as follows: Determine the relevant factors, then use those results to calculate a fund’s “neutral” performance.

A dumb and simple example is a one-factor model that measures funds solely by the amount of their equity exposure. If the stock market gains 5%, then a fund with a 100% equity factor would also be expected to gain 5%. (Dumb and simple, as I said.)

The difference between the fund’s actual return and its expected return, as forecast by the factor model, is called “alpha.” It can be positive, negative, or (if there is no difference) neutral.

Alphas occur for two very different reasons. They may arise because the model fails to specify all relevant factors. Or they may be caused not by the workings of the model, but instead by the portfolio manager’s decisions.

In investment analysis, these two causes are usually conflated, with alpha being interpreted as “the contribution made by the portfolio manager.”

This column will henceforth commit the same sin, with your author pleading a twin defense. First, the factor model is relatively accurate, as it reliably assigns to index funds alphas that are near zero. Second, the analysis concerns groups of funds rather than individual examples. Thus, the error terms tend to cancel each other out.

What Are Fund Alphas?

Onto the numbers. I used a factor model for all US diversified equity funds, including both indexed mutual funds and ETFs, for two five-year periods.

The first runs from 2013 through 2017 and the second from 2018 through 2022. The model used was the Fama-French three-factor model.

It accounts for:

- The amount of each fund’s U.S. stock market exposure,

- the size of its companies, and 3) their investment style (that is, to what extent the stocks may be described as “value” or “growth”).

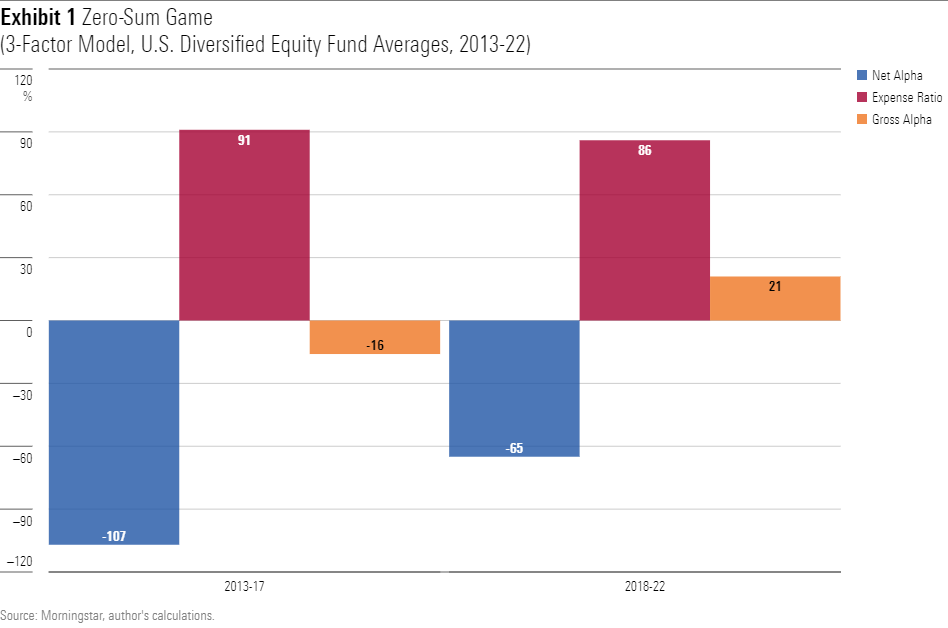

Bogle’s first and primary assertion is that investing is a zero-sum game. Every trade creates both a winner and a loser of equal size.

Back in the day, dissenters could plausibly argue that portfolio managers were the former and retail investors the latter. Not any more. Professional investors now account for 80% of stock market volume.

For the most part, portfolio managers compete against each other. The odds are therefore high that their aggregate alpha is something close to zero.

That is indeed what has occurred, per the three-factor model.

For the first period, the model calculated an average “net alpha”—that is, the alpha from the fund’s reported performance, which includes its official expenses—of negative 1.07 percentage points per year, or 107 basis points. Reimbursing funds for their expenses, to arrive at a “gross alpha” figure, leads to a much more modest deficit of a 16 basis points.

The average alpha increases for the second period. That improvement likely does not indicate true change in the fortunes of fund managers.

The factor model’s calculations are too imprecise to permit that level of analysis. But the key message is clear: Bogle’s first precept holds.

In general, US equity funds match their customised benchmarks before paying their expenses and trail them after those costs are considered.

(Note: In addition to expense ratios, Bogle listed trading costs as an obstacle for actively run funds. With brokerage commissions almost extinct, and spreads greatly reduced, that problem no longer exists.)

Do Positive Alphas Persist?

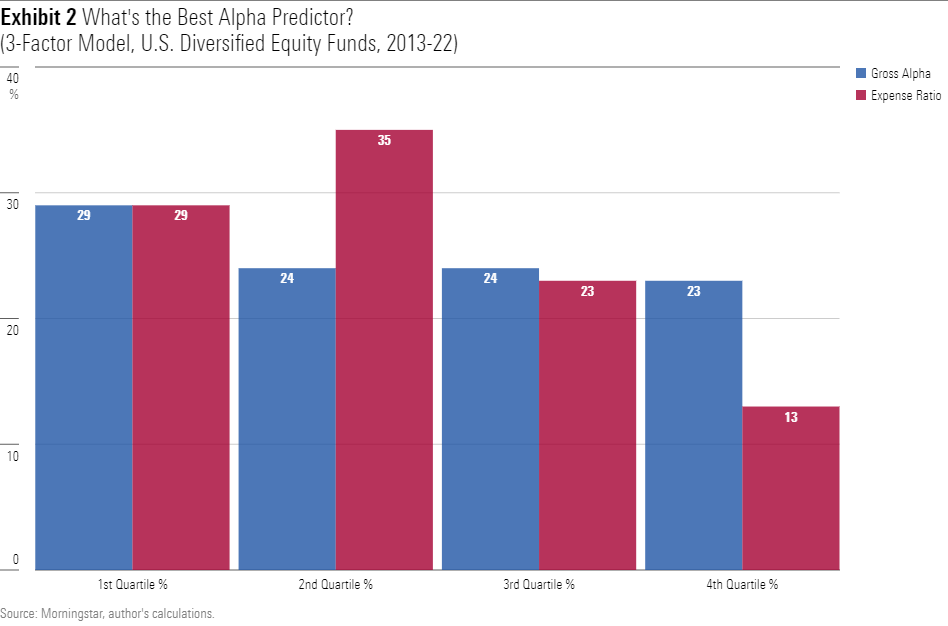

Bogle’s second and third axioms, which each concern predictability, can be addressed with one chart.

I sorted the 2013-17 fund results into quartiles, by:

- their gross alphas and

- their funds’ expense ratios.

I selected the top quartile of funds for each attribute, then scored how those two groups fared over the ensuing five years. The results appear below. The output consists of their net alphas, which were also sorted into quartiles. For example, 29% of the top-quartile funds from 2013 to 2017, as measured by their gross alphas, posted top-quartile net alphas from 2018 to 2022. Meanwhile, 22% landed in the bottom quartile.

Whew! That was boring to write. The point is, was Bogle correct that costs do a better job of forecasting future net returns than do assessments of manager skill?

Yes, he was.

Sorting by gross alphas proved mildly helpful; it would be inaccurate to state that the factor model’s result was entirely beside the point. But expense ratios clearly provided the stronger signal.

Although they were no better at identifying future top performers, they were much likelier to find above-average funds. They were also likelier to avoid the industry’s dogs.

Sometimes, as former NFL coach Chuck Noll would say, before you can win a game you have to not lose it.